5 Discussion

Entrepreneurship has been defined as interpreting situations differently and acting assertively to exploit such differences, often developing a venture with the goal to make a profit. This combination of thinking and doing puts the notion of action at the heart of entrepreneurship studies. The purpose of the appended studies was to examine the nature of entrepreneurial action, focusing specifically on how technology entrepreneurs experience risk, opportunity and the role of self as part of the venture creation and development process. Methodological focus was on the lived experiences of entrepreneurs. Such a focus is seen as a complement to existing research that prioritizes behaviors, cognitive mechanisms and narratives.

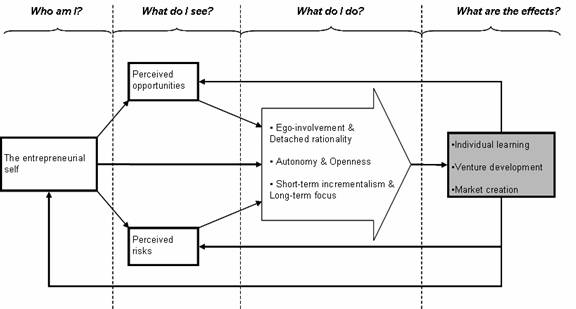

This section revisits the empirical results with an eye to identifying common themes that may be relevant for understanding entrepreneurial action more generally. These themes are found on a level slightly above the findings of the individual studies, which specifically explored risk, self and opportunity. Here the empirical results are instead reorganized in response to the more general research question: “How do entrepreneurs experience and conceptualize their actions in creating and developing their ventures?” Study II focuses mainly on the identity of the entrepreneur. Study I splits perceptions of risk into two broad categories: innovation risks encountered and affected. Study III similarly distinguishes between opportunities as perceived to be existing and created. Based on this very rough division, the empirical results (studies I-III) can be categorized according to the sub-questions: Who am I?, What do I see?, What do I do? (see Table 2). The discussion is thus grounded in the empirical categories from studies I, II and III. Study IV is set in a corporate environment and is brought in during the discussion to contrast and support the findings.

|

Who am I? II-1 - Innovator’s reflexive

self-conception II-2 - Innovator

ego-involvement II-3 - Commitment and control

II-4 - Personal stakes II-5 - Cognitive strategies

of the self |

What do I see? I-1 - Human capital I-2 - Pace and priority I-3 - The world moves III-1 - Exploiting knowledge III-2 - Filling the gap III-3 - Opportunity in

timing |

What do I do? I-4 - Activating social

networks I-5 - Risk learning I-6 - Risk incrementalism I-7 - Maintaining venture

agility I-8 - Creating and

sustaining autonomy III-4 - Enacting the

Zeitgeist III-5 - Stability as

strategy III-6 - Sequential entry

process |

Table 2. A recategorization of the empirical results from studies I–III.

Building on this empirical categorization, it is possible to connect the results in an analytical model of entrepreneurial action (Figure 3). This model also includes an outcome box that corresponds to the question: What are the effects? This is more of an analytical extension of the model. The results contain discussions of effects and outcomes. But because the outcome box is not directly based on the empirical findings, it is shaded in the model. It is included because it rounds off the model and because specifying relevant outcomes improves analytical clarity (cf. Davidsson 2004: 129-130).

The arrows in Figure 3 indicate causal relationships. Since the methods used in the studies are not longitudinal, the suggestion of causality may be criticized. The empirical material is rich and in itself contains discussions of temporality and cause-effect relationships. Still, the causality suggested by the arrows is mainly an analytical elaboration that organizes the entrepreneurs’ experiences into a logical sequence.

The structure of the model is similar to that of the causal model outlined in Chapter 1.1. The causal model describes a logical flow starting with individuals whose perceptions lead them to take certain actions (e.g. Krueger 2003). While the general structure of the model resembles this broad schematic, the specific findings, i.e. the content of the boxes and their internal relationships, are grounded in a more situated understanding of action (e.g. Brown and Duguid 1991).

Figure 3. A tentative model of

entrepreneurial action.

This model illustrates how entrepreneurial action can be analytically understood as a cycle that starts from the entrepreneur’s historically and socially developed self, which influences what stand out as relevant and interesting risks and opportunities. Perceptions of risks and opportunities allow the entrepreneur to suspend the ongoing flux of experience and use them as temporary points of orientation for further action. Perceptions of risks and opportunities thus become relevant as part of different practices and enactment strategies. Here the entrepreneur draws on personal experiences and interaction with the surrounding context to elaborate and reinterpret the perceived risks and opportunities. In action the entrepreneur is able to elaborate and test ideas, explore uncertainties and develop vague and private hunches. The outcomes of these activities are brought together under the headings of individual learning, venture development and market creation. Entrepreneurial actions continuously feed back into the entrepreneurial self, thereby forming the backdrop for future perceptions of risks and opportunities. By developing the venture and creating new markets, risks and opportunities are also influenced more directly.

In the remainder of the chapter, this model is elaborated by relating previous theory with examples from the appended studies. The discussion is structured along headings that correspond to the themes found in Figure 3. As mentioned, the components of the model are more analytically than empirically distinct. This is because action is seen as an ongoing accomplishment that cannot be divided into thinking and acting (see Chapters 1.1 and 3.1). As a result there is some empirical overlap between the different components of the model.

5.1 Who am I?

‘Who is an entrepreneur?’ has been a major question and point of debate in entrepreneurship studies. Early entrepreneurship research sought to ground explanations of entrepreneurial action in specific personal qualities or contextual pressures (Shane 2003). In recent years, heterogeneity regarding knowledge, preferences, abilities and behaviors has emerged as a fundamental assumption in entrepreneurship theorizing (Gartner et al. 1992, Venkataraman 1997, Davidsson 2004). This is reflected in economic theorizing where the relative importance of entrepreneurs seems to be linked with a far-reaching ‘subjectivism’ (see Chapter 2.1).

An important challenge is to provide a theoretical grounding for heterogeneous entrepreneurial subjects that can account both for the individual and for the social (structural) without simply pinning the two against each other. To this end the self was introduced as an alternative lens through which to regard the entrepreneur (study II). In the psychological tradition, the self is seen as the particular being or identity that distinguishes one individual from others. The present discussion rests on a more sociologically influenced view where the self is seen as a mix of subjective identity, which is spontaneous, personal and creative, and internalized roles that correspond to the organized attitudes of wider groups. The self is thus not exclusively an expression of the individual, but of a dynamic form of subjectivity that is constructed in the interface between the individual, his/her surrounding world and the activities that evolve there.

The studies showed that entrepreneurs tend to bring a whole range of ‘non-entrepreneurial’ ambitions, role identities and network ties to bear on their activities, e.g. by invoking personal experiences as well as multiple identities as researchers, owners, friends and family providers to frame situations or motivate decisions (II-1). This resonates well with Steyaert’s (2004a) plea to regard the entrepreneurial subject as depending on more or less public discourses. It also recalls O’Conner’s (2004) study which shows how entrepreneurs reconstruct their identities in accordance with different venture storylines.

The last example highlights the dynamic nature of the entrepreneurial self. With time and experience the answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ will gradually change, as some experiences are likely to take on more enduring forms in terms of habits, heuristics and specific knowledge (Shane 2000, Sarasvathy 2001, Mitchell et al. 2002) as well as social roles and identities that entail certain values and behavioral expectations (Hoang and Gimeno 2005). The answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ therefore suggests an answer to the question ‘What do I see?’.

5.2 What do I see?

If entrepreneurs are seen as heterogeneous, this has obvious consequences for what stand out as relevant risks and opportunities in different situations. The status of such perceptions constitutes one of the main controversies in entrepreneurship studies at the moment, namely whether opportunities (and risks) have real existence independently of entrepreneurial interpretations (Shane 2003) or whether they are in fact created as part of the entrepreneurial process (Sarasvathy 2004b) (studies I, III).

The studies show that entrepreneurs often describe risks and opportunities as objectively existing. In study I the entrepreneurs described objectively existing risks in terms of human-relations issues such as finding competent personnel (I-1), issues of timing including first-mover risks (I-2), and the unruliness of the world, which may manifest itself in unpredictable markets (I-3). Opportunities were similarly described as more or less given in the existence of attractive knowledge of different kinds (III-1), gaps in different social and organizational structures (II-2) or in divergent development tempos, e.g. between promoted and existing services (III-3). These broad categories also contain perceptions of more concrete risks and opportunities.

As much as individual perceptions may correspond to different underlying conditions, e.g. technological discoveries or markets trends, the focus on ongoing action rather than static choice downplays the ontological distinction between what is real and what is perceived (Weick 1995). Perceptions of relevant risks and feasible opportunities drive action whether these reflect ‘objectively true’ risks and opportunities or not (Krueger 2000). The main role of risks and opportunities is consequently to impose some form of order on the venture development process – to provide cognitive and practical drivers or ‘points of orientation’ that more or less temporarily guide entrepreneurial actions under conditions of uncertainty (Gartner et al. 1992). Perceptions of risks and opportunities provide lenses through which the past is seen as coherent and which also entail visions of plausible futures (cf. Steyaert and Bouwen 1997, Lane and Maxfield 2005). Vivid perceptions of opportunities are, for instance, important reflexively to energize the individual entrepreneur, and in social situations entrepreneurial charisma and confidence inspire people both within firms (Witt 1998) and on markets (Langlois 1998a). It seems that perceptions of risks and opportunities provide drivers of actions regardless of their correspondence with reality (studies I, III). This was also evident in study IV where organizational structures and attitudes affected risk perceptions and perceived risk management options.

Not all actions are preceded by clear perceptions of what to do. Action is to a great extent guided by ‘situational intentionality’ (Joas 1996) or ‘skillful coping’ (Dreyfus 1991) where people more or less intuitively respond to emerging situations without much conscious deliberation. Not even having explicit intentions guarantees a consistent sequence of intention, action and outcome (Weick 1979, Brunsson 1993). Consequently, when entrepreneurs act they are guided by both explicit perceptions and more tacit intuitions.

5.3 What do I do?

As indicated above, perceptions of risks and opportunities become truly relevant when understood as part of ongoing action. This section extends the previous questions, Who am I? and What do I see?, by outlining three entrepreneurial enactment processes recurring in the empirical material. The following sub-chapters thus describe the tensions between ego-involvement and detached rationality, venture autonomy and openness, and finally the trade-off between short-term incrementalism and long-term focus.

5.3.1 Ego-involvement and detached rationality

This heading describes the tension between a very personal involvement and more detached modes of engagement. While passion is an important aspect of entrepreneurial action, entrepreneurs sometimes need to detach themselves from their ventures. This may be very difficult and, to attain the necessary detachment, entrepreneurs were found to recall or construct temporary identities that allowed them to suspend their own feelings, for instance when making important decisions.

In the category ‘Personal stakes’ (II-4) the reasons for being an entrepreneur were described as a mix of existential, emotional and social factors. The entrepreneurs did not see themselves as primarily risking alternative costs or some potential profit. Instead what was at stake and what influenced many actions was the entrepreneur’s complex self-identity, which had to be upheld vis-à-vis colleagues, family and reflexively to an ideal image held by the entrepreneur of himself or herself. This is similar to the findings of Hoang and Gimeno (2005) who argue that people’s beliefs about prototypical entrepreneurial characteristics and activities will influence actual behavior. The findings also extend this perspective by describing how ‘non-entrepreneurial’ factors influence entrepreneurial actions.

The category ‘Enacting the Zeitgeist’ (III-4) further illustrated how entrepreneurs sometimes use highly visceral interpretations or feelings of personal excitement to legitimate opportunities. This recalls the parenting metaphor (Cardon et al. 2005) with its emotional connotations. Sometimes decisions and actions are not grounded in cost-benefit analyses but in “emotions and deep identity connections between an entrepreneur and an idea or opportunity” (Cardon et al. 2005: 24).

This issue is explicitly addressed in the category ‘Innovator ego-involvement’ (II-2) which describes how personal engagement can be very important in terms of producing commitment and resolve. Regarding the venture part of one’s personality leads to a form of ego-based or existential stubbornness that allows the entrepreneur to focus on a given vision and prevail in the face of tremendous turbulence and negative feedback. In the literature this is sometimes seen as a fortunate consequence of cognitive biases. The typical argument is that entrepreneurs ‘suffer’ from illusion of control, high levels of optimism, or affect-infusion (Baron 1998, Simon et al. 2000) and that, while objectively irrational, such ‘unsubstantiated enthusiasm’ is in fact necessary for entrepreneurship to take place (Busenitz and Barney 1997). Others suggest that creative action cannot be thought of in terms of deviations from objective rationality (Sarasvathy 2004a) and that strongly believing and consequently acting ‘as if’ risks are negligible and opportunities rich is often rational and functional from an action perspective (Gartner et al. 1992, Brunsson 1993).

|

|

|

“Perhaps I discard an economically

successful alternative. I may focus on myself and thereby short-change the

company as a whole.” (II-2) “You get so into what you do … like phone

ring tunes […] It is so cool to get the phone to sound different, cool

graphics on a screen … to get the weather report in your phone. We thought it

was really freaking cool what we did” (III-4) |

There are of course potential drawbacks to high levels of ego-involvement. Many entrepreneurs become blinded by the brilliance of their own ideas and, besides being a tremendous source of vitality and inspiration, love can also be blind (Cardon et al. 2005). This may be especially true for technology entrepreneurs, who often start with elegant technical solutions that are allowed to unduly constrain the perceived market, development of business models and so forth.

The

importance of a more detached analytical stance is evident in the category ‘innovator

ego-involvement’ (II-2). As

mentioned, some entrepreneurs experienced a form of identity overlap and had trouble

separating their personal identities from the venture. To retain a proper business

focus, entrepreneurial ego-involvement must therefore be managed. As indicated

in the first quotation above (

The category ‘Risk learning’ (I-5) shows how entrepreneurs invoke specific experiences and learned role-identities (cf. Hoang and Gimeno 2005) from work in academia and different corporations as more ‘objective’ backdrops against which to make sense of the present entrepreneurial process. By invoking an image of the entrepreneurial process as ordered, the entrepreneurs could increase their self-confidence (Krueger 2003) but also allowed a distanced comprehension of their own role in the overall process.

The instrumental use of multiple identities or discourses was further emphasized in the category ‘Innovator’s reflexive self-conception’ (II-1). Here it is shown how entrepreneurs more or less actively trade off different real and imagined identities and roles against one another to reinterpret situations, overcome obstacles and take actions. This adds an active or reflexive dimension to the insight that entrepreneurial identities are discursively embedded (Lounsbury and Glynn 2001, Downing 2005).

|

|

|

“I look at the company as an owner; I will

be part of it as long as I contribute. In later phases others are probably

more suitable.” (II-2) “The outlook I had with me from

experimental physics was important here […] to develop something towards a

long-term goal in a complex environment. It’s important to master your path,

but not necessarily the totality of it all.” (I-5) |

To summarize, entrepreneurial action in many ways depends on a high level of personal engagement. This engagement, which is often grounded in social and existential factors, is important not least because it allows entrepreneurs to act on personal visions, inspire others and carry novel ideas through in the face of uncertainty and negative feedback.

Ego-involvement also needs to be monitored. Entrepreneurs were found to draw on previous experience, formal theories and different role identities in a self-reflexive ‘sense and sensibility’ trade-off that allowed them to deploy their personal commitment in productive ways.

5.3.2 Autonomy and Openness

The second tension concerns autonomy and openness. Autonomy is both an existential need and more importantly a set of practical strategies for shielding the innovative integrity of the venture. The strife for autonomy is also moderated by a balanced and necessary infusion of external influences.

The category ‘Creating and sustaining autonomy’ (I-8) describes a range of strategies by which entrepreneurial actions avoid becoming too restrained by external forces. Entrepreneurs take a number of measures that shield the venture from external pressures and allow it to develop in relative autonomy. These measures can be practical, as when unspecified sources of funding are used to pursue pet projects or when external audits are used to increase the integrity of the venture. The results of such measures are often tangible, e.g. more resources or financial capital. What is perhaps even more important is that they produce a perception or ‘sense’ of autonomy and strategic freedom. Perceived autonomy and freedom over one’s work process has generally been associated with creative results, even when overall goals have been set externally (Amabile 1998). This insight also receives support from study IV, which illustrates how perceived and real control over one’s work process relates to conceptions of risks to organizational innovation.

The results thus extend the general ‘need for autonomy’ from being an existential need or a character trait (Delmar 2000) to also comprise a set of practices that protects the venture from harmful influences while at the same time sustaining a sense of innovative integrity in the venture.

|

|

|

“Too little and too dedicated money is

another risk. We took money budgeted by S (public utility) for machine

purchases and used part of it for developing the innovation. […] It’s easier

to obtain forgiveness than permission.” (I-8) “I tried to get my academic colleagues to

shoot down the idea on several occasions, but it withstood their attempts.

That way I figured the technological risk was accounted for.” (I-8) |

While autonomy and integrity are certainly important, a balanced infusion of external stimuli is also needed. External contacts serve to provide novel impulses. They also provide the kind of creative balance between novelty and social appropriateness that signifies innovative entrepreneurship (Lounsbury and Glynn 2001).

The category ‘Activating social networks’ (I-4) describes how entrepreneurs open up the borders of their ventures and use the resources and legitimacy of both professional and personal networks to increase flexibility and the range of available options. Previous research recognizes this practice, as entrepreneurs have been shown to use private and professional networks both to assess risks and spot novel opportunities (Johannisson and Mönsted 1997, Jack and Anderson 2002). The results (I-4) further show that by engaging an extended network of people, including financiers, consultants and potential customers, entrepreneurs are able to act as if their ventures are larger than they really are. This is in line with behavioral findings indicating that market interaction and highly visible activities tend to increase the likelihood of venture success, but also failure depending on the venture’s original potential (Carter et al. 1996, Delmar and Shane 2004).

If instead entrepreneurship is seen as truly creative, an inviting attitude toward external actors contributes much more than tests and validations of pre-existing opportunities (study III). On such an account, openness and interaction instead fuel a creative process in which the identities of the entrepreneur and the venture (O’Connor 2004), as well as the external environment itself (Weick 1979) are jointly renegotiated as part of the venture development process (Sarasvathy 2004a, Lane and Maxfield 2005).

|

|

|

“In this field one can have almost as many

partnerships as one likes. Many partnerships, for instance with consultants,

spread the risks and cover up the holes in competence and in the market.” (I-4) “NN has activated several strategic actors

by describing visions. Now we have to deliver.” (I-4) |

To summarize, entrepreneurial action requires both autonomy, e.g. to focus and reflect, and openness, e.g. to ensure appropriateness and fuel the creative process. To this end, entrepreneurs use a range of strategies that sustain a measure of autonomy while at the same time allowing the venture to be influenced by inputs from external stakeholders.

5.3.3 Short-term incrementalism and long-term focus

The final enactment process regards the trade-off between short-term incrementalism and flexibility and the need to retain a long-term focus.

Opportunistic adaptation and incremental learning strategies are often promoted as essential in the face of uncertainty (Bhidé 2000, Honig et al. 2005). These qualities were also prominent in the category ‘Risk incrementalism’ (I-6). Uncertainty forced many entrepreneurs to engage in a form of short-cycle experimentation to develop the venture. This should not be confused with playing it safe or an aimless muddling through strategy. Overall goals are often ambitious, but high levels of uncertainty force the entrepreneur to put the bulk of the effort into tactics and execution. Amar Bhidé contrasts entrepreneurship with strategic management and replaces the classical chess metaphor with poker, since entrepreneurs “play each hand as it is dealt and quickly vary tactics to suit the conditions” (Bhidé 1986: 62).

The category ‘Maintaining venture agility’ (I-7) describes how undertaking a wide range of venture activities keeps the venture ‘on its toes’. At the core of this category is the realization that the future is not given. In contrast with the previous category, the entrepreneurs here proactively experiment with parallel product tracks, different business models and alternative future scenarios to build up momentum. This allows entrepreneurs to fend off risks ‘on the fly’ and move the venture swiftly in different directions by dint of internal preference or external demands. This recalls Lane and Maxfield’s (1996) recommendation to foster ‘generative relationships’ in the face of short planning horizons.

Also the category ‘Commitment and control’ (II-3) reflects the importance of taking action in the short term, not least as a way to overcome uncertainty. This idea of ‘acting one’s way out of uncertainty’ is reflected by many authors including Gartner et al. (1992), Bhidé (2000) and especially Sarasvathy (2001) who argues that creation of control through action is often preferable to prediction under conditions of uncertainty.

|

|

|

“The venture is our baby, not the technology.

Risk management to us is therefore maintaining a clear business focus and to

constantly seek out new products and services. We will not become rich from

[product name].”(I-7) “The most dangerous thing that can happen

is decision anxiety. We would rather be wrong four times out of five than

make the right decision too late.” (II-3) |

Long-term strategies are often not available for entrepreneurial firms. This may be due to practical reasons such as poor cash flow (Bhidé 1986) or simply because the future is inherently uncertain (Shackle 1979). Still, short-term incrementalism needs to be balanced against some form of stable core or vision for the company, whether in terms of technology, market or business model (Sjölander and Hellström 2005). This becomes apparent in the category ‘Stability as strategy’ (III-5). This category describes different strategies for achieving a sense of stability and permanence in the venture. Entrepreneurs are thus able to withstand external turbulence by focusing on areas of perceived stability, whether these consist of sticking with given customers, focusing on ‘obvious’ values or organizing venture operations around the current staff. Entrepreneurs thus impose their own sense of structure by highlighting features that they control. In this way they reduce the perceived uncertainty of the future, which in turn enables more confident actions (Sarasvathy 2001). ‘Sequential entry process’ (III-6) recalls the preceding category. Here entrepreneurs take strategic positions in either markets or technologies with the hope that these positions will pay off in the future.

Deciding on a long-term goal clearly provides the venture with a sense of focus and direction. Long-term focus can thus be seen both as a practical issue that guides specific actions and as a way to cope mentally and emotionally in the face of great uncertainty. The latter aspect was clearly evident in the category ‘Cognitive strategies of the self’ (II-5), which describes how entrepreneurs envision glorious prospects, for either present or coming ventures, as a means to deal emotionally with a stressful present. This resonates with cognitive biases like affect-infusion (Baron 1998) and overconfidence (Busenitz and Barney 1997). It also qualifies general findings by emphasizing how such cognitions are moderated by specific situations and purposes.

|

|

|

“Everyone believed in this, they thought

it would come. We realized that if one positions oneself now, one will surely

be in a good position later” (III-6) “We are really just trying to maintain

what we have and grow nice and slow. You shouldn’t create any problems, so to

speak … now if we expand these areas we will do it one per quarter or one

every six months, so you build them and let them sink in” (III-5) |

To summarize, entrepreneurs take short-term actions and renegotiate their strategies in response to emerging situations. This is often necessitated by the uncertainty of the future and lack of resources. It can also be part of a proactive strategy where the entrepreneurs incrementally create the future. Entrepreneurs also balance the short-term activities with some sense of long-term focus. This can be achieved by focusing on perceived areas of stability or by envisioning a glorious future as a way to justify current hardships.

5.4 What are the effects?

The previous chapters drew on the empirical findings to elaborate entrepreneurial action in terms of who entrepreneurs are, what they see, and what they do. The present chapter extends this to also include the question of effects or outcomes. Even though the empirical material contains discussions of effects, this chapter is not based on empirical evidence to the same extent as the previous ones were. Nevertheless, a discussion of outcomes is included for reasons of analytical completeness and clarity.

The problem of identifying suitable effects or outcome measures plagues most social sciences, and may be especially pressing in entrepreneurship studies where the process is open-ended making goals quite fleeting. Entrepreneurship is also linked to many levels of analysis including the individual, the venture and the greater situation of which it is part. Next, the question ‘What are the effects?’ is therefore addressed in relation to the interrelated themes of individual learning, venture development and market creation.

Individual learning

What constitutes individual entrepreneurial learning is a point of some debate. The cognitive tradition focuses on the development of context independent schemas or scripts that capture the lessons learned from precious experience (Mitchell et al. 2002), whereas discursively oriented writers argue that learning is more about becoming familiar with specific local settings and communities (O’Connor 2004).

This study has sought to bridge the focus on cognitions or discourses by emphasizing that entrepreneurial action is in many ways a form of meaningful and situated reflection-in-action. While the study design precludes any verdict as to what constitutes functional practices, the results indicate that individuals take actions that merge individual ambitions and contextual conditions in a way that is perceived as meaningful to the stakeholders involved. This resembles the focus on functional and useful practices and strategies suggested by authors like Lane and Maxfield (1996) and Sarasvathy (2001). The findings in the thesis contribute to these efforts by suggesting that such practices need to balance the tensions between ego-involvement and detachment, autonomy and openness, and short-term versus long-term focus. Besides bridging cognition and discourse, the focus on individual learning as development of practices links individual learning to the more concrete issue of venture development.

Venture development

Since new ventures typically seek to create value together with external stakeholders, it has been argued that venture development is mainly about establishing an appropriate business model. A business model describes the logic by which a venture should be organized to match resources and customer needs in a way that generates appropriable value. This very general statement has been operationalized as the answers to a series of questions including: What value propositions or offers can be articulated, based on the available technological resources? What existing or new customer segments can be identified? What specific offerings can be developed? What value chain is suitable to produce the offer? In what value network should the firm be positioned? What revenue mechanism should be used to capture value from the offer? (cf. Chesborough and Rosenbloom 2002, Andrén et al. 2003, Sjölander and Hellström 2005).

These questions seldom have clear answers, and taking actions to answer one will typically change the conditions for addressing the others. As a result, business models gradually develop as the result of experiments and interactions with different stakeholders. In this process it has been argued that all aspects of the business model cannot change at the same time (Sjölander and Hellström 2005). A similar conclusion may be drawn from study III.

As successful ventures mature and grow, business models often become more rigid. This shift may reduce the role of individual perceptions, as the venture becomes increasingly integrated with external actors.

Market creation

Over time the venture becomes more and more constrained by its network of related actors including customers, suppliers, financiers and strategic partners who, with time, will influence what the venture is about and constrain what it can do (O’Connor 2004). This reminds of institutional theory. What signifies entrepreneurship is that this influence is very much reciprocal and that entrepreneurial action also influences institutions. The actions undertaken by the entrepreneur in many ways modify, and in some respects create, the surrounding environment. By expanding the venture and enlisting others while doing so, entrepreneurs in a very real sense enact the world and its institutions (Gartner et al. 1992) not least by creating new markets and business models (Sarasvathy 2004b).